Update: Understanding Iowa's jobs deficit

Posted on July 23, 2021 at 3:41 PM by Colin Gordon

On June 12, Iowa ended its participation in federal pandemic-related unemployment programs. Those relying on the $300 dollar/week bump under the federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (PUC) program saw their weekly benefit slide back to pre-pandemic levels, an amount that replaces only about half of lost wages.

The self-employed Iowans relying on Pandemic Unemployment Assistance benefits, and those receiving extended (beyond 26 weeks) benefits under the Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation (PEUC) program lost their weekly benefits entirely.

This is a penalty Iowa’s governor has imposed on her own unemployed constituents. Governor Kim Reynolds’ pretext for this decision, announced May 11, is a need to “address the State of Iowa’s severe workforce shortage.” In this view, the only obstacle to full-blown economic recovery was the generosity and security of unemployment benefits. “Iowa is open for business,” Iowa Workforce Development Director Beth Townsend wrote in her memorandum recommending this decision, “and we must take all necessary actions to assist with that recovery by returning Iowans to the workforce as quickly as possible.”

The official narrative strains credulity, as well as the basic principles of economics. We do not have a shortage of workers. We have a shortage of safe, living wage jobs.

When the COVID recession began in February 2020, Iowa had 1,590,900 jobs. In April 2020, at the trough of Iowa’s recession, Iowa had 1,412,500 jobs — a contraction of more than 10 percent. Fourteen months later, in June 2021, we were still 71,100 jobs short of pre-recession levels (as of January 2020; see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Iowa still climbing back from pandemic job losses

So where did all the jobs — or all the workers — go?

In June 2021, 66,400 Iowans were unemployed but looking for work. Of these, it should be noted, only about one-third (about 22,000 as of the last weekly report) were receiving unemployment benefits. Reynolds and Townsend would have us believe, as long as jobs are going unfilled, that those benefits are somehow illegitimate.

There are three things wrong with this view.

First, it assumes that any worker can slide into any job opening. Yet there are many reasons — including qualifications, transportation, health, or family commitments — that might stand in the way. A single mother in Ames cannot be expected to pick up an evening shift at Hy-Vee in Ankeny just because it is available.

Second, workers make choices about entering or leaving the labor market based on other considerations — including the safety of themselves and their families. Iowa’s unemployment program allows workers a “good cause” quit, and eligibility for benefits, if the conditions of work are unsafe. But, as the record of Iowa’s Occupational Health and Safety Administration (underscored by not confined to meatpacking outbreaks) makes clear, the state has largely abdicated this responsibility.

And third, it assumes that the fault lies with the worker and not with the terms of the job that is going unfilled. The one clear and powerful indicator of a labor shortage is rising wages. When anything is in short supply, its price increases. The fact this this is not happening suggests the problem is not “I can’t find workers” it is “I can’t find workers at the dismal wages I am offering.” In turn, the quality of available jobs has eroded. Workers may be reluctant to commit to a job, even at decent wages, when job security is thin or scheduling is unpredictable.

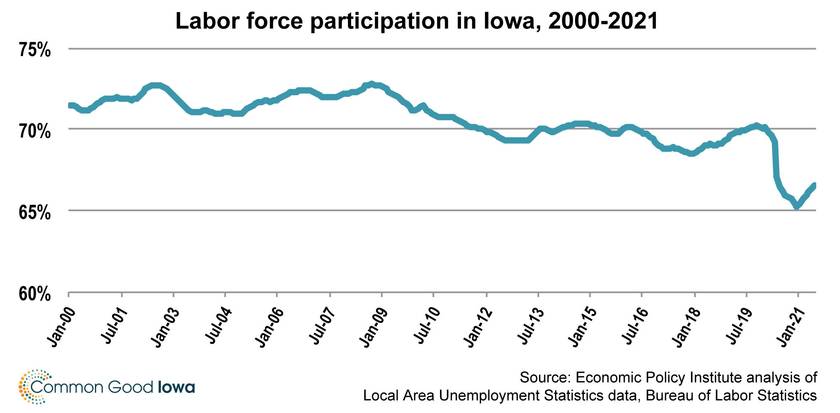

But, by far the single largest group of “missing workers” are those who have dropped out of the labor market altogether. Between February 2020 and June 2021, Iowa’s labor force participation rate (the share of the population 16 and older that is working or looking for work) fell from 69.9 percent to 66.6 percent (Figure 2). Only five states (Vermont, Connecticut, Virginia, Maryland and Ohio) saw steeper losses across that span.

Figure 2. Largest group of ‘missing workers’ out of labor force altogether

These workers are disproportionately women. The COVID-19 recession hit particularly hard in sectors like retail, leisure and hospitality where women make up the bulk of employment. Those sectors have been slow to rebound and the job quality is generally poor. In turn, women took up most of the caregiving slack created by operations issues in schools, child care centers, and long-term care facilities.

All of this underscores the cruel folly of slashing the federal unemployment benefits. Of Iowa’s missing or reluctant or unemployed workers, only a small fraction are even “incentivized” by this decision. For those workers, the evidence is clear that a few extra weeks or a few hundred extra dollars a week are not the real obstacles to re-employment. And, for those workers and everyone else, the evidence is equally clear that there are good reasons — including other commitments, and the quality and safety of the jobs going begging — not to leap at the next “help wanted” sign.

Colin Gordon is a senior research consultant for Common Good Iowa. He is a professor of history at the University of Iowa and author of CGI’s State of Working Iowa analysis.

Editor's Note: This post updates a previous post, from May 25, 2021.

Categories: Covid-19, Data, Jobs & labor, Safety net & work supports